Special Issue: Part 6

(Un)Common Landscapes and Ruptured Memories: Auto-ethnographies of North Bengal

Talking of Colonial Narratives and Peoples Histories

Aparajita De and Rajib Nandi

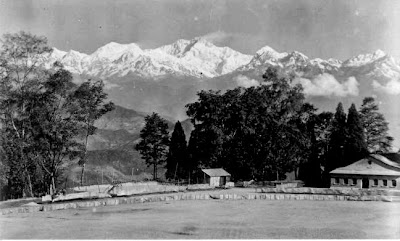

Aparajita: You know, whenever one talks of North Bengal, it is

Darjeeling - the snow-capped mountains, beautiful forest bungalows, tea estates

that comes to one’s mind. Next is Siliguri and NJP (New Jalpaiguri Station). So

whenever I told someone that my husband is from Siliguri, who was born in Naxalbari

…there was no apparent excitement… just the opposite a sudden dead silence. One

obviously associates Naxalbari with Naxalbari movement and Naxalism. I always

wondered what it was like to be born in Naxalbari… to live in a place that gave

its name to a movement, movement of a particular type… radical and

revolutionary. So how do you see the place Naxalbari and your life there…how

long did you live there?

Rajib: Yes I was born in Naxalbari where I spent the first ten

years of my life before moving to

Siliguri. When I was born, the movement had just started. It began sometime in

May 1967, and I was born in October 1968. So obviously, I can’t remember the first

few years of the movement…though heard much later from my mother on the earlier

days of the movement. But definitely few scenes of early seventies still remain

fresh in my memory.

We used to live on the ground

floor of a two-storied building and our small sitting room used to open out to

the main road through a large square verandah. Once, I remember I was playing

there alone in the evening and suddenly I heard noises … loud slogans… Naxalbari

Zindabad…Inqulaab Zindabad. I came running to the middle of the road and saw a

large procession, hundreds of people maybe, with torches in their hands,

bows and arrows, spears, sickles… it seemed as if they were coming towards me. I

was very scared that day, somehow I quickly ran back to the veranda. In another

incident during the same period, one morning when I came out to the verandah, I

saw the white walls of the verandah being written in black tar. I had just

learnt to read but one line I still remember even today … “jotedarer matha kata

jaabe…” [the jotedar’s (zamindar’s) head would be chopped off]. When we were

growing up in Naxalbari we often heard that so and so person, mostly young men,

who were in hiding … had fled to Nepal or Assam to save himself from police

arrest.

Anyways, I really enjoyed my childhood in Naxalbari for many other reasons. It was a beautiful place surrounded by forests, tea gardens and paddy fields criss-crossed by several streams. I still cherish those days, our long walks with my father towards Panighata- east of Naxalbari.

Anyways, I really enjoyed my childhood in Naxalbari for many other reasons. It was a beautiful place surrounded by forests, tea gardens and paddy fields criss-crossed by several streams. I still cherish those days, our long walks with my father towards Panighata- east of Naxalbari.

I started my studies in the

primary section of Nand Prasad School that was the only high school of

Naxalbari at that time. Interestingly my classmates were Nepali speaking boys

and girls, Adivasis like Oraon, Santhal, and of course Rajbanshis and Bengalis.

I still remember Bene Oraon, one of my good friends in primary school. One more

thing I remember from early seventies…refugees from east Bengal. Often we used

to hear about families having just come from Pakistan.

If you look at the history of

Terai region, the region where Naxalbari is situated… historically it was a contested

land between Nepal and Sikkim. But it was always a land of many people and many

communities…. This area ..the whole of Terai and Dooars, from River Mechi in

west to River Sankosh in the east.

Aparajita: What strikes me is… what was it about Naxalbari that

gave birth to a movement like this. How did it start, who were the people, were

they really involved with this? Why this particular type of movement started here

and not elsewhere?

Rajib: There is a history of peasant movements in North Bengal.

Naxalbari was not the first rebellious movement. From mid- 40s a series of

peasant uprisings had taken place. You might have heard about the Tebhaga

movement. Apart from Tebhaga, there were a few other smaller movements here and

there. However, among them Naxalbari definitely got a different kind of

attention from media and scholars. Perhaps for many reasons, which I think we

don’t have the scope to discuss here. A culture of peoples movement did exist

much before Naxalbari happened. But I would like to mention here that the

geographical and political location of Naxalbari was one of the key strategic

reasons for Naxalbari uprisings. It is a bordering area with Nepal, Bihar,

Bangladesh, Sikkim…strategically an ideal place for the revolutionaries to hide.

The peasants who participated in the movement were mostly from various adivasi

communities. Among them, the adivasis from Chhota Nagpur, who used to constitute a

large part of the movement, were originally brought as tea coolies by the planters. Later the

tea sector could not recruit all of them. The surplus labourers became the

adhiars (share-croppers), and consequently became a large part of the peasant

communities of North Bengal. There is plenty of literature on the agrarian

structure of North Bengal, the conditions of peasants and share- croppers,

vulnerable occupancy rights of the peasants and how the share-croppers used to

be exploited by the jotedars…and how the peasant movements intensified in

various parts of India including Bengal. Some argue, over a period of time,

numerous struggles against such exploitation led to the emergence of Krishak

Sabha, the organization that mobilized peasants on several occasions and then

Naxalbari.

When I grew up, in early to mid-70s,

not much was actually happening in Naxalbari, as far as peasant movement is

concerned. Because, by that time the movement in West Bengal had already spread

to urban centres including Calcutta. But police was active with many arrests

taking place.

Aparajita: You know being born in Calcutta, I am an outsider to North

Bengal, though my family came from East Bengal during partition, …. we

visualized North Bengal, as Darjeeling and the tea gardens, Dooars and the Wildlife Sanctuaries like Jaldapara …all

of which are made by the British. As if, there was nothing before the British

came in. I mean there were no people, there was no local history… a wild kind

of a place. When you talk about the indigenous people, we had no knowledge

about them and often by indigenous; we assumed it to be the adivasis, but they

too were settled there by the British. The only non-British thing we were aware

of was the Cooch Behar Royal Family…and again they were highly colonized. They shared

good relations with the British. Even, a Cooch Prince was married to a daughter

of Keshav Chandra Sen, a famous social reformer of Calcutta…just a royal

family…as if beyond that nothing existed.

Rajib: Definitely, it’s a popular imagination of North Bengal,

particularly of many Bengalis outside North Bengal. So when Kamatapur movement

started in the late-90s, people started thinking from where did this movement

come…Bengalis used to think that only Bengalis live there, people other than Bengalis

were the Nepali speaking people in the hills and the adivasis from Chhota Nagpur

in the tea estates, all from outside….

Aparajita: You are right. When you say Rajbanshis and Kamatapur

movement, I distinctly remember a television show from that period when KPP

(Kamatapur Peoples Party) and KLO (Kamatapur Liberation Organisation) were active. It was a discussion with a few Rajbanshis who

were demanding the separate state of Kamatapur on the basis of the language –

the Kamatapuri language. They claimed that their language pre-dates Bengali and

is different from Bengali and everybody at home almost exclaimed in utter

horror…what is this person saying?...This is not a different language this is

only a different Bengali dialect nothing more than that…and there was this

utter disbelief that it could be a different language and that it was too older than

Bengali… and even in the show this disbelief was rife amongst the other participants.…

Rajib: I think that’s a different debate, whether Kamatapur or

Rajbanshi language is a part of Bengali or a different language altogether. The

politics of formation of a language and claiming/reclaiming of a language is

totally a sociological issue….nothing to do with linguistics or grammar. Languages

are born first, grammars are written much later. Every language has strong links

with other languages. The boundaries are often blurred. Two different languages

may look very similar, their grammars might look similar, because two languages

which are recognized as different languages today, might have been born from

one common language. If you look at histories of languages, you will find this

everywhere.

But I would like to highlight one

thing very clearly. North Bengal is a part of an ancient culture of eastern

India. It has a very strong pre-British history. Why it’s known or why it’s not

studied in school or college text books.. that’s again a separate issue. But,

yes the Bengali history in North Bengal largely began only during the colonial

period, as far as top three districts of North Bengal are concerned. Once the

British administration started development in the form of tea plantation,

extension of railways, forest conservation, various other government offices,

and also in the Cooch Behar native state, Bengalis started coming in search of

white collar jobs, as office babus and for small business opportunities.

Therefore, the Bengali history in North Bengal starts during the colonial

period. However, there were already histories existing; if not in the form of scientifically

documented histories; but in the form of folk traditions, in poetics, in the

form of oral histories, and myths. But they may not be recognized as legitimate

or formal form of histories…but these things were there. Interestingly, the

histories written by the colonial ethnographers and surveyors or by the

historians of colonial period became the official history of North Bengal. From

late eighteenth century you know, there were a lot of surveys and ethnographic

studies by the British ethnographers and surveyors. And these eventually became

the authentic histories and ethnographies of North Bengal.

Aparajita: I find one thing very amazing, whenever I go and talk to

people here, whether in a seminar or any other gathering or social media sites, I am always astonished by the number of people quoting and referring to colonial

literature…Hamilton, Dalton, Sunder, they always mention these surveys at some

point of time or the other. And these people are not academics but are ordinary

people from various occupations. And would then elaborate that such and such babu

who helped that sahib for that survey, he himself wrote another book later…and

they will come and say, do you want a photocopy of this? And he will happily

give you a photocopy as well.

Rajib: Yes, that’s an amazing feature of North Bengal. There are a

lot of local authors in North Bengal. The tradition may have started by a very

few pioneering people, one of them being Dr. Charu Chandra Sanyal. Several

others followed suit. Strangely a ‘supposedly’ unknown past always haunts the

people of North Bengal and to know this unknown past, they heavily rely on

colonial literature. It comes back again and again in the local literature.

They cannot write without referring to the colonial literature. Even if they do

not believe in the colonial version, they love to mention it, they often contradict

it by adding another small piece of history to it. An unknown history and the

quest for it to mark North Bengal for its uniqueness.

Aparajita: An unknown history and an unknown past… hmmm and

Bengalis, and here I may add more particularly that Kolkata based Bengalis see

North Bengal as part of it and yet outside Bengal. It’s like a far away distant

land which is exotic and its not only the scenic beauty that attracts Bengalis but

it is that unknown exotic past that attracts them most…you fear it and at the

same time you love it as well. Fear and Love both enmeshed into one another.

This is something, which I see reflected in the people of North Bengal themselves.

So when they discuss and write…they are in a way trying to rediscover

themselves by rewriting the past. And while engaging and rewriting the past; the

colonial archives play a central role.

The colonial literature, sort of

establishes a kind of valid or perhaps official histories and archives. But

apart from them, different kinds and forms of histories get enmeshed - the

documented with the undocumented ones. There is a beautiful blending of these two

when local people start writing their own histories. They bring something more

to colonial ethnography along with local narratives. Whenever I talk to someone

here, they say if you are so interested, I have published an article, and then

they will happily pass on a photocopy of the article. Everybody has written

something or other. No matter what he/she may be… an engineer, a doctor, a clerk, a

shopkeeper, a school teacher…..

Rajib: Why do you think this particular culture developed there?

Aparajita: Its not just Bengalis, I find Rajbanshi, Rabha, Boro,

Nepali everyone from various backgrounds, occupations writing their own

histories… But I don’t have an answer as to why … no answer at all.

Rajib: Perhaps it’s an unending process of rediscovering one’s self

and history. Possibly also because it’s a transitional zone, it’s got borders everywhere…

multiple political and ethnic borders. It’s not just one political border but

many overlapping borders … So many ethnic groups and so many ethnic borders

that overlap. Historically, lots of people belonging to

different communities and regions travelled through this land, from west to the

east … from north to south and vise versa.

Aparajita: It’s almost like a gateway…that’s why this region I

think is called the "Dooars…the Doorway" to Bhutan, Sikkim and doorway to the

west from Bihar to UP, and a doorway to the south the larger Bengal plain…so it’s

almost a region that opens out in all directions. It’s an interface an area of constant

interactions …

Rajib: That’s why I call this place a cultural frontier…different

people came here at different points of time…lived here…and moved to another

place after a period of time…so the borders are very blurred. You won’t find

distinct borders here…even the borders between the ethnic groups.. between the

languages…are very blurred… that’s the reason it is difficult to distinguish

Bengali from Kamatapuri.. Not only the language, but if you look at the

communities…sometimes you cannot differentiate one from the other. In a recent

facebook page started by some Kamatapur supporters, I saw the other day, they

themselves initiated a new argument, why the Koch and Rajbanshi now; have become

Koch-Rajbanshi. And they themselves started contradicting their own histories

of the name ‘Rajbanshis’ that was brought into public debate one hundred years

back by Rajbanshi Kshatriya Samity. One has commented in the page that the name

‘Rajbanshi’ was actually invented by the British ethnographers and census

officials rather than the people themselves. He further argued that the

original name of the people is ‘Koch’ instead. A Rabha man, in a rejoinder wrote,

“I am a Rabha, but Rabhas are also known

as Koch”. He further argued, “Are we,

the Koch and the Rabha, same people?” All these prove that the ethnic

boundaries are too blurred to differentiate. In another incident, during my field work in Dooars

in early 2000, I heard a common legend from Rabha, Mech, Garo, Toto, Rai, Limbu

that all of them were actually brothers once. They came from Tibet, lived in the

Himalayan foothills and finally they chose different paths, got separated and

eventually became known in different names.

North Bengal is an interesting

place as far as its history is concerned. It’s even more interesting, when you

look closely at the historical process of history making. The identity of this place,

which is known as North Bengal today has always been challenged and contested...from

Pragjyotisa to Kamatabehar to North Bengal, as is the identity of its people. Peoples' identities are often fragile and ever changing. Moreover, peoples' involvement

in the writing, re-writing and re-interpreting of its history and identity is

amazing. This uniqueness of this place gives birth to a particular type of

political culture…you may say a kind of politics of resistance.

Aparajita: I think the political culture and the politics of resistance

that you say, takes the shape of people, local commoners, writing their own

histories. That’s why I think the auto-ethnography approach or methodology

takes on a different meaning here. Because it’s not just a self narrative, a

simple writing of one's own history but

it is the dissenting voice of self from the margins resisting

outsiders…colonizers who are writing for them, be that the British in the

colonial period or the Bengalees in the present context.

(The conversation is part of a

larger book project on North Bengal and the making of its local history)

Authors' Bio- Note:

The author is an Assistant Professor in Department of Geography, Delhi School of Economics, University of Delhi.She is also the Convenor of the Department's Media Lab and Digital Library. She is currently working on Mediaspace, Bollywood and Popular Culture.

Rajib Nandi is a Research Fellow at Institute of Social Studies Trust, New Delhi and holds Ph.D. in Social Anthropology from Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. His areas of research interests include Social movements and Environment.